Abstract

The mediatization of communicative action is a process that centrally moderates social change. Changes in communication (e.g., through new kinds of media) thus have momentous consequences for social forms and processes. As essential cultural signs, social bodies, their medial representation, and areas of society in which bodies play a role are interrelated with changes in communication. Currently, physical self-representations in digital media play a key role and hold strong possibilities of influence on the culture of sports and movement. The aim of this study was to identify the effects of visual self-representations in social media on this culture. Following an integrative review methodology, we systematically organised the current state of empirical evidence and identified the implications that digital self-representations in social media (esp., Instagram, Facebook) have on sports and movement culture and therefore possibly on physical education (PE). Six electronic databases, reference lists, and citations of full-text articles were searched for English and German language peer-reviewed articles. The search string combined different terms relating to social media and sports culture. Two independent reviewers screened all identified studies for eligibility and assessed the methodological quality of the included studies. The results point to direct changes in some sports and movement cultures such as the prosumtion (consumption and production) of videos in skateboarding or the perpetuation of body ideals in the fitness culture. Other sports and movement cultures are changed indirectly via different new use cases for the athletes, as they can use social media to either build communities or gain visibility. As the practice of prosuming bodily self-representations is a growing part of the lifeworld of adolescents, such practices could become content within PE. Therewith, students could acquire competencies that allow them to intellectually relate to these practices, which could help them in understanding, changing or transcending their existing realities.

Keywords

social change, mediatization, body image, physical education

Introduction

The content dimension of learning is an essential factor in planning, implementing and evaluating school lessons (Amade-Escot, 2006; Kansanen & Meri, 1999). Compared to science subjects (e.g., natural sciences, languages), the issues of learning in physical education (PE) are primarily based on social phenomena within the students’ lifeworld (Amade-Escot & O’Sullivan, 2007; Zander, 2017). Although the question of which specific sports and movement cultures should become objects of PE is discussed academically in diverse ways and takes on different forms in international curricula (e.g., traditional sports, basic themes of movement, trend sports, fitness activities, media sports), the underlying aim of PE is that students physically experience cultural practices that are of significance in their immediate lives, gain competence to act within these practices, and to intellectually relate to these practices in order to understand, change or transcend existing sports and movement cultures (Ehni, 1977; Nyberg & Larsson, 2014; Serwe-Pandrick et al., 2023; Siedentop et al., 2019).

As structures and functions of social forms and processes are constantly changing (Corsi, 2020), the content of PE oriented towards social phenomena is also exposed to constant possibilities of adjustment. Besides globalisation, commercialisation, and individualisation, mediatization centrally moderates social change in modern society (Krotz, 2014) and also significantly influences sports and movement cultures (Ličen et al., 2022). In this regard, the common practice to position and present pictures of bodies on social media might also impact sports and movement culture (Grimmer, 2017, 2019; Sanderson, 2011), which in turn might also have consequences for the content of PE.

Within our integrative review, we focus on the practice of physical self-representation on social media and synthesize the international state of research on this social phenomenon. We specifically examine how such practices might have changed sports and movement culture, which generates an empirically sound basis for the development of content within PE as the practice of physical self-representation on social media is particularly common among adolescents (Pürgstaller, 2023).

Theoretical background

Changes in society through mediatization

Within the social sciences, mediatization is one of the processes discussed in the context of social change as it temporally, spatially, and socially penetrates our lives (Hjarvard, 2008; Krotz, 2014). According to Lundby (2014), mediatization denotes a dynamic process that indicates transformation on technical, institutional, and cultural levels. Through the increasing permeation of society with new forms of media communication, mediatization leads to various processes of social change that can be characterised as “extension, substitution, amalgamation and accommodation” (Schulz, 2004, p. 88).

Consequently, changes in communication, especially through the spread of new types of media (e.g., letterpress printing, steam engine, electrification, internet, social networks), can have significant implications for cultural forms and processes, such as the composition of social fields, cultural symbols, social organisations, value systems, patterns of inter-human relationships, and rules of conduct (Corsi, 2020). As social bodies are essential cultural symbols, changes in communication are interrelated with their medial representation, which in turn also might have consequences for those areas of society in which the body plays a significant role (Lin & Atkin, 2007). In this way, sports and movement culture as well as PE, due to its orientation towards social phenomena within the students’ lifeworld, are directly affected by changes in the media.

Mediatized changes in modern sports and movement culture

Sports and movement culture, is decisively associated with the body and its physical representation since the organised and non-organised communication of the achievements of the human body is its defining characteristic (Stichweh, 2013). With sports and media being intertwined historically (Werron, 2010), mediatization denotes a significant moderator of change in the sports and movement culture (Frandsen, 2020; Whannel, 2013), affecting it on an individual, organisational, and societal level (Ličen et al., 2022). Advances in technology have enabled the widespread use of previously expensive devices for various practices of self-tracking (Rode & Stern, 2019; St. Clair Kreitzberg et al., 2016). The accessibility of high-quality cameras and user-friendly editing software has also impacted the sports and movement culture, particularly with regard to the promotion of specific movement practices within trend sports (Dupont, 2020; Woermann, 2012). Further, athletes are using social media to communicate with fans and engage in public relations (Utz, 2019), while also aligning their behaviour significantly with media expectations (Birkner & Nölleke, 2016). Leagues and clubs have reacted to media demands by converting their stadiums into “giant television studios” (Altheide & Snow, 1991, p. 224) and establishing their own media training departments. Some sports have been adapted to the logic of mass media through the “telegenisation of sporting events” (Schauerte & Schwier, 2004, p. 164), in which competitions are dramatized and dynamized (e.g., shortening of race courses, modified rules and materials, adapted forms of competition) so that the events are more attractive to the media.

One major area in which sports and movement culture has been deeply affected by mediatization in recent years is the self-representation of the body in social networks, which is particularly common among children and adolescents. Motives for this “bodily image practice” (Pürgstaller, 2023, p. 55) on social media differ. Some people may aim to present the (often toned and sculpted) body to others, while others may aim to associate themselves with certain types of sport (Rode & Stern, 2019; e.g., producing videos relating to a specific style or publishing self-tracking data from running apps; St. Clair Kreitzberg et al., 2016) to establish a specific social identity (Schmidt, 2009; Wheaton, 2019). While these identity-forming physical self-representations have so far largely been performed in analogue public spheres, the mass distribution of digital social media has recently provided an additional stage for self-presentation.

Significative physical self-representations in social media

Bodily self-representations in different communicative arenas are of social significance, enabling an analysis of society and social change. As a social symbol, the body fulfils different functions (Gugutzer, 2006). On the one hand, it serves as “a personal front” (Goffman, 1956, p. 15) for the production and communication of social identities in direct interactions. On the other hand, the body and its representation provide indications of shared realities regarding the prevailing social order in society (Stadelbacher, 2016). Social structures impact the design (e.g., tattoos, piercings), the presentation (e.g., permissible permissiveness), the shape (e.g., cosmetic surgery, muscle gain) and the meaning of the body (e.g., object of research, status symbol), and also influence which bodies can be shown publicly (Butler, 1990; Villa, 2008).

Social media offers an unprecedented possibility of depicting the social body and thereby transmitting information. Like bodies in direct analogue interaction, bodies presented in social media inform “about the actor’s social attributes and about his conception of himself, of the others present, and of the setting” (Goffmann, 1963, p. 34). Thereby, bodily self-representations in social media provide a means of identity formation and communication. Oftentimes, displaying the body in social media aims at obtaining social approval and creating a sense of belonging (Nadkarni & Hofmann, 2012), which is why many social actors use impression management strategies to create a desired persona for the audience (Fox & Vendemia, 2016).

However, bodies are not only shaped by society and thus stabilise the existing social order, they can also be designed and positioned to change social order. In this regard, bodies and their re-presentation exert influence particularly on those areas of society in which bodies play a significant role. As more and more athletes, for example, stage physical self-presentations and post bodies on social media, these representations hold potential for changing the sports and movement culture, particularly if the bodily self-representations challenge existing structures (Stanley, 2020), provide platforms for new forms of expression and identities for subsequent generations (Lee & Azzarito, 2021), or trigger changes in routines of action (Stern, 2019).

Building on the steadily expanding mediatization of sports and movement culture and its potential for social change, an increasing number of studies that analyse physical self-representations of athletes in social media has emerged in recent years. However, the existing studies are limited to individual facets, scattered across different scientific disciplines, and have so far been compiled in a cursory manner at best (Grimmer, 2017, 2019; Sanderson, 2011). With our integrative review, we therefore aim to systematically analyse the empirical body of research on physical self-representations of athletes in social media. Specifically, we aim to assess whether and how physical self-representations of athletes in social media signify changes in the sports and movement culture.

Methods

We adopted an integrative review methodology based on the principles described by Dhollande et al. (2021). Integrative reviews allow for the synthesis of diverse research methodologies (e.g., theoretical, experimental and/or non-experimental empirical research, and qualitative, quantitative and/or mixed method studies) and demand applicability of the results to practice, which is why they are particularly relevant in the fields of medicine, politics, or in education (Whittemore & Knafl, 2005). As the research on physical self-representations is a diversely researched field encompassing research from various disciplines and theoretical orientations, we decided to conduct an integrative review (instead of a systematic or scoping review) as we interpret this type of review as being most open to different research methodologies and due to its emphasis on the applicability of results to practice. The practical implications of our integrative review are directed towards the PE context, as our review is framed in terms of education.

Search strategy and eligibility criteria

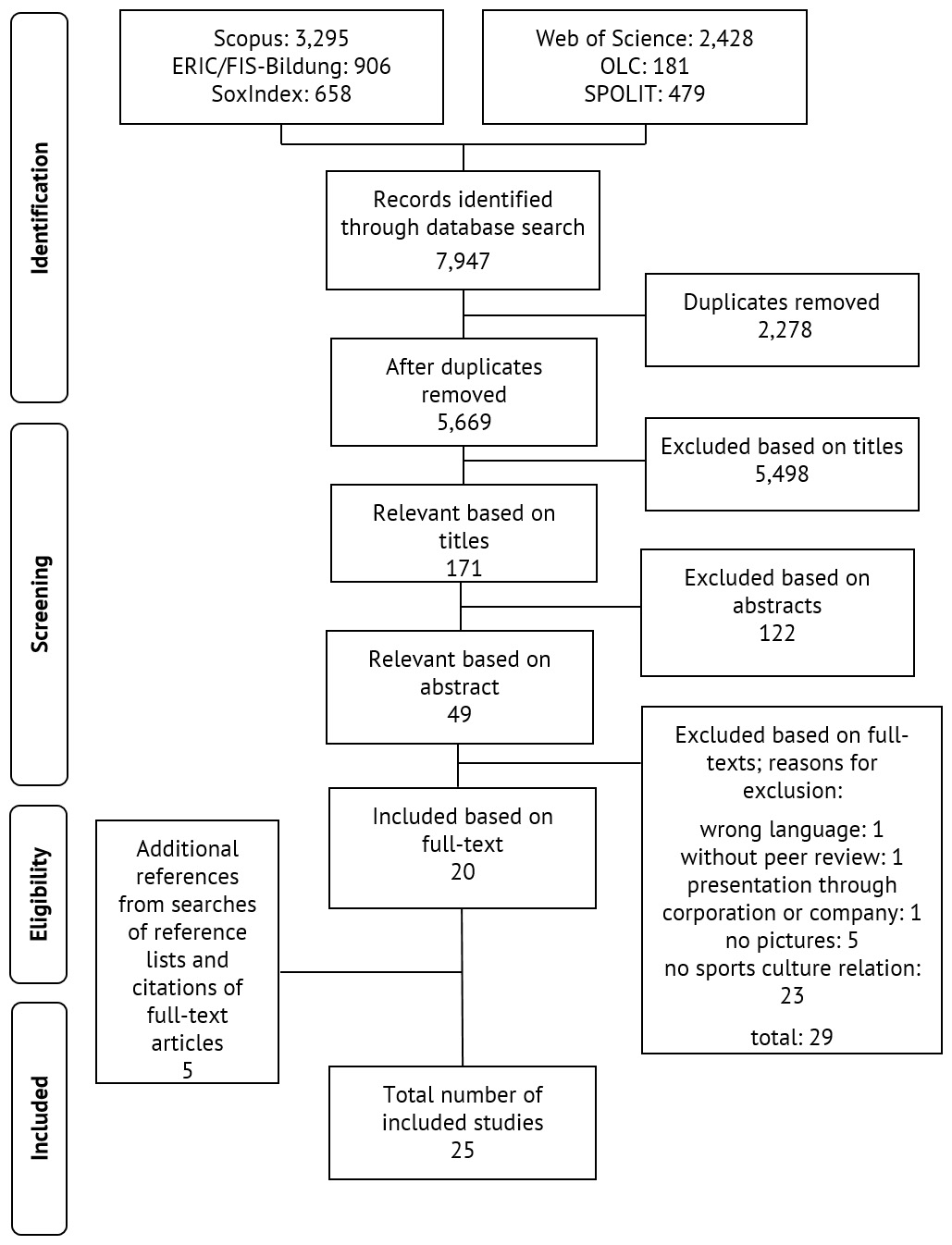

The search string combined terms related to the sports and movement culture (sport* OR physical activity OR physical culture OR movement culture OR athlete*) and relevant terms in the context of social media (social media OR sns OR instagram OR facebook OR youtube OR tiktok). The search was conducted on 2 February 2023 via six electronic databases: Web of Science and Scopus (general databases), SocIndex (sociology), OLC (media and communication studies), SpoLit and FIS-Bildung (sport science). Additionally, reference lists and citations of the included papers and relevant theoretical papers were screened to identify further studies.

The following eligibility criteria were compulsory for the studies to be included in the review:

primary or secondary empirical research works published in peer-reviewed journals in English or German (the languages each author speaks);

content of the study related to the sports and movement culture and social media;

analysis of types of social media that allow for user generated content and are focused on pictures;

analysis of real pictures with (self-)representation of bodies;

analysis of publicly visible pictures (no private accounts);

studies related to physical activity that exceeds everyday/household activities.

The publication period was set to the period since the founding of Facebook until today (2008-2023). Since we aimed to analyse the empirical body of research on physical self-representations on social media, we only included empirical papers in our review. As most empirical studies nowadays are published in journals, we excluded other types of publications. In line with our research question focusing on physical self-representations of athletes on social media, we excluded papers examining PE. Studies addressing marketing and branding or how social media can be used to increase motivation for physical activity were also excluded from the review.

Study selection, data extraction, and analysis

After a carefully conducted stepwise literature search, the results were exported to Citavi, a reference management software, and duplicates were removed. Two independent reviewers (FM, DJ) screened titles, abstracts, and full-texts for eligibility. To not miss relevant literature, reference lists and citations of the included papers listed in Web of Science and Scopus and relevant theoretical papers were reviewed to identify additional studies. At each step of the process, any discrepancies regarding inclusion or exclusion of studies were consensually resolved by discussion.

The extracted data included:

study characteristics (author, date of publication, journal, objective of the study, discipline of the researchers, and research design);

sample characteristics (type of sports, sample size, geographical location, social media type, and gender);

study design (including data collection methods and data analysis methods);

main outcomes of the studies.

When essential information was missing from the full-texts, the corresponding authors were contacted to obtain the missing details. The search and selection processes were illustrated in a flow chart (see Figure 1). The main descriptive characteristics of the studies were outlined using a detailed table (see Table 1). The relevant results of the included studies were narratively synthesized. To this end, we inductively analysed the findings of included studies and sorted the findings in overarching categories. Therewith, we were able to synthesize the results of individual studies in a systematic and comprehensive fashion.

Quality appraisal

Each article meeting the eligibility criteria was critically appraised to judge the methodological quality. As studies based on different methodologies were included, we used a scoring system for appraising qualitative, quantitative, and mixed method studies (Pluye et al., 2009). Following the guidelines set by the appraisal tool, a percentage quality score was generated for each study, dividing the sum of positive responses (i.e., specific criterion was fulfilled) by the number of relevant criteria. All articles were independently assessed by two authors (FM, DJ) and were then discussed until consensus was achieved. Cohen’s kappa was calculated as a measure of initial inter-observer agreement.

Results

The initial literature search resulted in 7,947 hits of which 2,278 were duplicates. The remaining 5,669 results were screened based on the title, after which one hundred seventy-one titles remained. After abstract screening, 49 studies were included in the full-text audit. Twenty studies met the eligibility criteria. The reference search and the cited-by-search resulted in the addition of five studies. After methodological quality assessment, all 25 studies were chosen for the integrative review (see Figure 1).

Methodological quality

Initial inter-rater reliability on all assessed studies was almost perfect (ϰ = 0.93; McHugh, 2012). For all deviations, complete agreement was reached by discussion. Most studies implemented a qualitative research design (n = 15; 60%), followed by quantitative designs (n = 9; 36%) and mixed method designs (n = 1; 4%). Overall, the studies had a decent methodological quality, with quality scores ranging from 50 to 80 percent and most studies being located in the upper range. No study was excluded from the review due to methodological reasons. The included qualitative studies show rather low levels of reflexivity, which could be attributed to the disproportionate frequency of qualitative content analyses, which show a stronger proximity to a quantitative paradigm compared to more reconstructive approaches (Holtz & Odağ, 2020). For the quantitative approaches, the appraisal criterion related to the assessment of confounding variables could often not be applied due to the rather observational character of the studies. Again, a dominance of content analytic study designs was evident. In two studies, the basic population remained unclear (Hinz et al., 2021b, 2021a). The results of the methodological quality assessment are presented in the Supplemental material, Tables 1-3.

Descriptive characteristics

Table 1 provides a summary of the descriptive characteristics of the included studies. The dates of publications range between 2012 and 2022, with 14 studies published in the last three years. Most of the studies were conducted in a defined geographic area. Only eight studies analysed posts from all over the world. The most represented country was the United States.

Most studies analysed physical self-representations on Instagram (n = 18). Two papers researched content from YouTube (Kassing, 2018; Woermann, 2012) and one from Facebook (Toffoletti & Thorpe, 2018). Four studies analysed media content across multiple platforms. Most studies (n = 16) searched for content online and used posts from the social network sites (SNS) directly, while others (n = 6) conducted interviews or collected survey data. Three studies combined online and offline content within an ethnographical approach. Eight studies focused on specific physical self-representations of specific athletes, while the other studies (n = 17) assessed physical self-representations of members of online communities that used specific hashtags (such as #yogaforall or #fitspo).

Source | Sport | SNS | Country | Study design | Sample | Methodology | Main results |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Yoga | worldwide | qualitative | 257 posts #YogaForAll and #YogaForEveryone | Collection of posts/reflexive thematic and discourse analysis | Community – creating a global habitus | ||

Fitness | SNS | United Kingdom | qualitative | 77 adolescents | Group interviews/thematic analysis | Visibility - Deficits in society | |

Fitness | worldwide | quantitative | 510 Images from 51 Fitspiration websites | Collection of images/content analysis | Community – creating a global habitus | ||

Basketball | USA | qualitative | Three posts from one black, lesbian celebrity | Collection of posts/analysis via “critical reading of visual body texts” | Visibility - Deficits in society | ||

Skateboarding | USA | qualitative | 40 male skaters | Ethnography with online and offline content/coding with GTM | Community – creating a global habitus | ||

Climbing/ running | Finland | qualitative | 10 Finnish climbers and runners | Collection of interviews and posts/content and image type analysis | Community – Elimination of gatekeepers | ||

Yoga | worldwide | quantitative | 740 images tagged with #yoga, -women, -practice and -body | Collection of pictures/content analysis | Community – creating a global habitus | ||

Yoga | worldwide | quantitative | 380 videos tagged with #yoga, -women, -practice and -body | Collection of videos/content analysis | Community – creating a global habitus | ||

Soccer | YouTube | USA | qualitative | Three videos of three former collegiate female soccer players | Collection of videos/thematic and comparative analysis | Community – creating a global habitus Visibility - Deficits in society | |

Fitness | worldwide | x | Interviews and Instagram data from 76 Participants | Questionnaire and collection of posts/statistical analysis of correlations | Visibility – individual athletes | ||

Mountain bike | SNS | USA | qualitative | 60 Interviews, 2,363 surveys and 98 e-mail exchanges | Collection of data/Coding with GTM | Community – Elimination of gatekeepers | |

Figure skating | Canada, Ukraine | qualitative | 122 posts of Meagan Duhamel and Aljona Savchenko | Collection of posts/dialogical narrative analysis | Visibility – individual athletes | ||

Fitness | USA, Canada | quantitative | 50 Instagram posts tagged with #amputeefitness | Collection of posts via Netlytic/content analysis | Community – Elimination of gatekeepers | ||

Paralympics | USA, Canada | quantitative | Instagram posts from six Paralympians | Collection of posts/content analysis | Visibility - Deficits in society/ niche sports | ||

Paralympics | USA, Canada | quantitative | Instagram posts from six Paralympians | Collection of posts/content analysis | Visibility - Deficits in society/ niche sports | ||

Fitness | SNS | USA | mixed | 244 participants | Collection of survey and SNS data/content and statistical analysis | Community – extending the offline community online | |

Various sports | SNS | United Kingdom | qualitative | 12 interviews with UK-based elite sportswomen | Collection of interviews/thematic analysis | Visibility – individual athletes | |

Climbing | worldwide | qualitative | 32 professional or sponsored female climbers | Ethnography with online and offline content/coding with GTM | Visibility – individual athletes | ||

Fitness | worldwide | quantitative | 150 posts tagged with #fitspo | Collection of posts via Netlytic/content analysis | Community – extending the offline community online | ||

Soccer | Brazil | qualitative | 123 posts from the Brazilian women national team of soccer | Collection of posts/content analysis | Visibility - Deficits in society/ niche sports | ||

Hiking | USA | qualitative | 60 Instagram profiles tagged with #unlikelyhiker | Netnography/critical discourse and visual content analysis | Visibility - Deficits in society | ||

Various sports | Global North | qualitative | Instagram profiles of five female athletes | Collection of posts/feminist thematic analysis | Visibility – individual athletes | ||

Fitness | worldwide | qualitative | 155 posts of the Bikini Body Guide community | Collection of posts/compositional interpretation | Community – Elimination of gatekeepers | ||

Yoga | worldwide | quantitative | 300 images tagged with #curvyyoga and #curvyfit | Collection of posts/content analysis | Community – creating a global habitus | ||

Freeskiing | YouTube | German speaking countries | qualitative | 4 years ethnographic data of the Freeskiing Community | Ethnography with online and offline content/n.a. | Community – creating a global habitus |

Notes: Source (Authors and year of published study); Sport (the aspect of the sports and movement culture the study focuses on); SNS (SNS used to derive the data); Country (Country the study was based on/where the researchers live); Study design (qualitative, quantitative, or mixed method); Methodology (Methods used for data collection/methods used for data analysis), Main results

Main findings of included studies

In general, the review of the findings reveals notable evidence pointing to mediatized changes in sports and movement culture. In the following, we present a synthesis of the main findings of included studies. Single studies are mentioned in more detail to highlight distinct aspects. When synthesizing the findings of included studies, we noticed that findings can be categorized in two broader categories:

impact of social media on specific sports or movement cultures and

uses and functions of social media within mediatized sports and movement cultures in general.

Some studies presented results hinting to changes that are very specific to one sport and movement culture (e.g., exercise identity in the fitness culture; Liu et al., 2021), while other influences transpired the culture they originated in (e.g., building a community was not limited to the outdoor sports community but could be found in various contexts). This is why we adapted two main categories for the synthesis of the findings of included studies. The subcategories were also derived inductively from the results of the studies.

Impact of social media on specific sports and movement cultures

The influence of social media was mostly studied with regard to specific sports or movement cultures, which is why we summarise the findings for specific sports and movement cultures separately.

One group of studies analyzed physical self-representations in social media tangential to the fitness sector (n = 7), where three main impacts on the specific sports and movement culture can be identified:

Promotion of the ideal body: The images posted under #fitspiration represent a collective ideal image of the (female) body (e.g., thin and attractive), and can influence the viewers to focus on appearance or exercise for appearance-related reasons (Boepple et al., 2016). Young people are dismissive of the link between fitness and attractiveness, but still support the long-standing cultural view that slim bodies are more attractive (Bell et al., 2021). Under the #amputeefitness, one can also find images that emulate or perpetuate the same ideal (Mitchell et al., 2019).

Building “exercise identity”: Posting and following content on Instagram relating to physical activity can lead to a strong exercise identity, meaning that individuals identify themselves as “exercisers” and therefore regularly engage in physical activity. A strong exercise identity is positively associated with higher levels of physical activity (Liu et al., 2021).

Motivation by peer support: In researching the Bikini Body Guide (BBG) community, Toffoletti & Thorpe (2021) found that posting images within the community led women to experience feelings of pride, pleasure, vulnerability, and authenticity as they depicted their bodies losing weight and getting stronger. Further, posting images helped the women in achieving their appearance goals more effectively. Santarossa et al. (2019) illustrate the possible influence of peers on exercise and eating habits. Their study shows that Instagram posts of peers were more frequently liked than posts of non-personal accounts. Additionally, Pinkerton et al. (2017) demonstrate that people who regularly share content on SNS are often more physically active.

Examining its inclusive potential, four studies relate to yoga. Although #yogaforeveryone focuses on the inclusive idea, Bailey et al. (2022) illustrate that the yoga hashtag communities spread a desire for yoga on the one hand, while on the other hand continuing to centre and privilege the young, thin, white, non-disabled, and flexible yoga body. The studies from Hinz et al. (2021b, 2021a) came to the same results, adding objectification and lack of diversity to the list. The image of yoga presented within the content (performative and for advanced people) contradicts the basic idea of yoga and can lead to feelings of exclusion (online and offline). Nevertheless, there are hashtags that embody the basic idea of inclusion. Under #curvyyoga, images can be found that counteract the stereotypical representations and hence transcend obstacles, especially for higher-weight individuals (Webb et al., 2019).

As outdoor activities rely on the exchange of information about routes, spots or equipment, social media aids in finding and connecting to new people or staying in touch with old friends (Ehrlén & Villi, 2020; McCormack, 2018; Stanley, 2020; Woermann, 2012). This connection to people pursuing the same hobby achieved through social media is referenced in five studies. Therefore, social media impacted the outdoor sports community mainly with regard to connection.

Uses and functions of social media within mediatized sports and movement cultures in general

Beside describing the impact of social media on specific sports and movement cultures (such as yoga or fitness), the findings of included studies also highlighted the uses and functions of social media within mediatized sports and movement cultures in general. In this context, two main themes emerge: building community and gaining visibility.

Fourteen studies report on how social media can enhance the building of a community of like-minded individuals, showing three sub-aspects:

Increasing accessibility: The community on social platforms facilitates access to the scene as social media bypasses the gatekeepers and thereby makes the sports more accessible. Through social media, new communities can be found, extended, or maintained while bridging physical distance. Posting pictures can be used to inspire and motivate other members of the community, to spread information (e.g., on current conditions on site), and to strengthen social relationships (Ehrlén & Villi, 2020). This gives new members quicker access to initial contacts and important information (McCormack, 2018). The resulting communities can also be used to draw attention to shortcomings and to issue warnings to each other (Stanley, 2020). Social community can also be sought online to people with whom there is otherwise no connection by linking different hashtags and therefore different communities, such as the combination of #amputeefitness and #fitfam (Mitchell et al., 2019) resulting in online-only communities supporting each other to reach goals (Toffoletti & Thorpe, 2021).

Creating a global habitus: Particularly the studies on skateboarding and freeskiing highlight how the use of social media constitutes a typical practice within the scene (Dupont, 2020; Woermann, 2012). In both cases, the practice of consuming and producing videos is vital to one’s status in the subculture. Videos are not only watched, liked, and discussed on the various platforms but also in offline settings. In this way, a style typical of the scene is developed and authentic identities can be obtained, which, through social media, can be spread globally. Oftentimes, this scene-typical style then becomes vital for being included in the community. Another example for a global habitus that grants entrance in the community is found in the yoga community. While promising yoga is for everyone (Bailey et al., 2022; Webb et al., 2019), the pictures found on Instagram display a certain body type and level of advanced skill (Hinz et al., 2021b, 2021a), which can lead people to think, that they need this kind of body to be part of the community. The same goes for the community around #fitspiration, which endorses an idealized female body and sometimes even objectifies the female body. Also, SoccerGrlProbs builds a knowing community that can identify with the problems presented in the videos. While using humorous and ironic self-portrayals, a certain way of dealing with challenges is presented (Kassing, 2018), causing other players to act the same way.

Extending the offline community online: Social media can be used to stay in touch with people you know and keep them in the loop as part of “social integration” (Pinkerton et al., 2017, p. 16). This is vital for the people involved in the communities as the support of peers has a greater influence on exercise behaviour than other support gained online (Santarossa et al., 2019).

Eleven studies report on how social media can be used to gain visibility. Here, we identified three sub-aspects:

Visibility of individual athletes: Instagram can be used to present oneself as a person who exercises regularly (Liu et al., 2021; Santarossa et al., 2019), has a body that matches the body ideal (Boepple et al., 2016), or is skillful in a specific sports activity (Hinz et al., 2021b, 2021a). Gaining visibility can be advantageous for individual athletes on the one hand as it allows for more attention and therefore more opportunities for being sponsored (even if they are currently not competing due to pregnancy, see McGannon et al., 2022). On the other hand, the process of gaining visibility can bring a lot of challenges, especially for female athletes. They need to find a balance between not too much and just enough attention (Rahikainen & Toffoletti, 2022, p. 252). Not enough attention can lead to invisibility and therefore missing out on sponsors, but too much attention can lead to threats from male Instagram users. Pocock & Skey (2022, p. 7) used the term “appropriate distance” to describe how the participants in their study managed this conflict. Additionally, female athletes need to appear feminine, spread self-love, -disclosure and -empowerment (thereby creating a new ideal for female athletes), and position themselves properly (e.g., as experts in their sport: Silva et al., 2021), while at the same time arming themselves against (male) aggressions (Toffoletti & Thorpe, 2021).

Visibility for niche sports: Visibility for sports and movement cultures that receive less public attention can be changed through Instagram, e.g., the Brazilian women’s football team, who are barely noticed offline in comparison to the men’s team (Silva et al., 2021). Another example are the Paralympians posting on social media and therefore promoting the Paralympic games (Mitchell, Santarossa, et al., 2021; Mitchell, Van Wyk, et al., 2021).

Challenging social ideals and stereotypes: Visibility achieved through Instagram is also used to change stereotypical representations and challenge social ideals. For example, Brittney Griner tries to make black lesbian desire and relationships visible and apparent through her posts. In doing so, she challenges the attempts to sanitise and de-sexualise the sport (Chawansky, 2016). The self-portrayals of Paralympians show the athletes in athletic endeavours with most of their visual content framing themselves in an inspirational manner highlighting that they as athletes have the same physical competence as Olympic athletes. Thereby, para-athletes might aim to change society’s image of themselves (Mitchell, Santarossa, et al., 2021; Mitchell, Van Wyk, et al., 2021). The female athletes in the study by McGannon et al. (2022) challenge the social image of pregnancy and motherhood. By portraying their own bodies in motion, they show that pregnancy is compatible with athletic endeavors. With their posts, pregnant female athletes show that it is possible to balance motherhood and sports. Although self-portrayals influence the social ideal, they can also be used as a counter model. For example, Bell et al. (2021) show that young people distance themselves from the content of #fitspiration posts and consider the depictions as not desirable. They thus create their own concept of fitness that opposes the displayed extremes often found under the fitspiration hashtag. Female soccer players also use their visibility on social media to highlight the problems female soccer players face and to support other female players in dealing with the challenges of everyday (training) life (Kassing, 2018; Silva et al., 2021).

Discussion

With our integrative review, we aimed to systematically analyse how physical self-representations posted on social media can be seen as a sign of mediatized change in sports and movement culture(s).

State of research

The included studies show that Instagram is the most researched platform for physical self-representations through pictures. The findings of our review illustrate that the sports and movement culture is influenced by mediatization, however, to various extent and in various ways. Physical self-representations on social media can change specific sports and movement cultures (e.g., fitness, yoga, outdoor activities, skateboarding, freeskiing), particularly in the way in which they are practiced. Informed by a theoretical framework, our findings suggest that people use bodily self-representations on social media as a way to build social identities (Goffman, 1956) and gain visibility but also as a new form of communication (Corsi, 2020) and therefore building community.

Overall, the analysed change(s) in sports and movement cultures indicated in the included studies can be characterised as both direct and indirect (Hjarvard, 2008), affecting different levels of social systems (Ličen et al., 2022). The changes described in the studies appeared to occur independently of the corona pandemic and seemed to persist after Covid-related restrictions. Hence, the corona pandemic might have accelerated but not directly caused the observed changes in the sports and movement culture. However, as the included studies did not explicitly study the impact of the corona pandemic on mediatized physical self-representations on social media, further research is needed in this context. Further, existing studies of physical self-representations in social media were often selective in terms of specific sports cultures and can therefore be characterized as early attempts to understand a specific sports and movement setting. The associated intention to provide initial insights into a particular social field might also explain the frequent use of content analyses. For future research, it seems appropriate to dive deeper into the phenomena at hand, e.g., through more reconstructive qualitative methods or statistical methods that go beyond mere descriptive analyses. Moreover, especially the traditional and institutionalised areas of sports as well as team sports (only represented through soccer) are missing in the current state of research. In addition, research on the influence of mediatization on different groups of people within sports could also be expanded. For example, marginalised groups (in terms of their religion, race, or sexual orientation) or other stakeholders in the sports culture (e.g., coaches, officials) should be considered for a more comprehensive picture. Further, future studies could examine how the effects of physical self-representations on the sports and movement culture of a specific sport differ between countries.

Limitations

Some limitations of our review can be identified. We only included peer-reviewed journal articles published in English or German language listed in the screened databases. Studies in additional languages, grey literature or reports, and articles outside the scope of the selected databases were not included. Since publication cultures might differ between countries, we might have missed some relevant studies. We also acknowledge that further insights could be gained by broadening the search strategy and inclusion criteria. As we aimed to give an overview of empirical studies investigating how the practice of physical self-representations on social media signify changes in the general sports and movement culture, we decided to not include specific sports and movement cultures (such as yoga or outdoor sports) into our search string. Similarly, due to the review’s focus on empirical research, we did not include theoretical papers, even though integrative reviews would offer the possibility to do so. Both aspects offer starting points for future review work on the role of physical self-representation on social media for (specific) sports and movement cultures.

Implications for PE

A key characteristic of PE research is addressing acute societal and political challenges (Oesterhelt et al., 2020). Relatedly, the content of PE is often informed by social phenomena within the students’ lifeworld (Amade-Escot & O’Sullivan, 2007; Zander, 2017) with the aim to create students who are competent to act within social bodily practices and critically reflect, change or transcend existing realities (Ehni, 1977; Nyberg & Larsson, 2014; Serwe-Pandrick et al., 2023; Siedentop et al., 2019). As mediatization affects almost every facet of life, it is not surprising that sports pedagogy is also concerned with how media can be used within PE. In this regard, sports pedagogy differentiates between learning with media and learning about media (Bastian, 2017). Learning with media incorporates all the ways that (digital) technology aids in the processes of learning and teaching of motor skills, abilities and sport-related knowledge (for an overview of possible use cases see Greve et al., 2020; and Jastrow et al., 2022). Learning about media involves that students learn to critically and reflectively consider the consumed media and related digital spaces, worlds and tools meaning digital tools that provide support (e.g., apps), self-tracking, e-sports, and social media (Poweleit, 2021). With regard to learning about social media, two schools of thought can be identified. From the perspective of the disempowerment approach, students need to learn to critically evaluate the content of social media, as it could be potentially harmful (e.g., resulting in body dysmorphia or eating disorders). Another approach is to view social media from an empowerment point of view, where young adults can experiment with new identities and find alternative ways to stage the body that, for example, do not simply have to follow traditional models of beauty (Pürgstaller, 2023).

The results of this review show that social media influenced the sports and movement culture positively through building community and gaining visibility. Therefore, bodily practices on social media that aid in connecting with people and help to be seen and recognized could become part of learning about media within PE.

To initiate discussions with and among students, support a critical engagement with social media, and teach the bodily practices, teachers need to learn specific skills first. Following the concept of TPACK1 (Van Doodewaard & Knoppers, 2018), firstly, one needs to gain the technological knowledge (e.g., how to search for suitable and relevant content). Even though scrolling through the feed or reels is possible without specific searches, this is not the way to reach the full potential. Filter bubbles and algorithms influence what people see (Friedrichs-Liesenkötter & Gross, 2020, p. 3). To circumvent this, one must actively search for specific terms, people, or hashtags. Equally important is a critical selection of people and hashtags to follow. For this, criteria (such as authenticity, disclosure of sponsorship) should be discussed in school. As the studies within this review on specific hashtags show, specific hashtags are often associated with certain communities that share specific values and goals. Within PE, the underlying values and created habitus of certain communities can be analysed and discussed with students. In PE lessons, sports-related influencers who are worth following could be discussed as well as inclusive communities for the respective interests of the students. The second area is producing content. Various elements come into play here. One is the technical aspect, which will not be discussed here. Another aspect to be considered when posting content on social media, is that users have to decide how much information about themselves they want to reveal and who should have access to it. In PE lessons, the consequences of gaining visibility could be discussed with examples from female athletes and the perceived aggressions against them (Chawansky, 2016; Kassing, 2018; Silva et al., 2021). Another aspect is the selection of hashtags as a means to connect one’s pictures to a wider array of similar pictures and therefore connecting to a community. Together with the practices of choosing the same style and content for pictures this can help in building community with like-minded others.

Conclusion

With our integrative review, we were able to synthesize the highly diverse research field of physical self-representations on social media and examine how such practices have affected the sports and movement culture. Overall, the findings of the review illustrate that mediatization, particularly the common practice of posting pictures of the body on social media, has changed sports and movement culture. While some changes have been identified in relation to specific sport and movement cultures such as the fitness or yoga community, other changes transpired the culture they originated in and affected the broader sport and movement culture. More specifically, the synthesis of the studies suggests that the practice of physical self-representation on social media allows users to build community and gain visibility. As social media and bodily (re-)presentation on these platforms are part of everyday lives of children and adolescents, such practices could also be included into the curriculum of PE. In this regard, PE could teach a reflective and critical use of these practices to mitigate the risks of visibility on social media and facilitate the positive effects of online communities.