Abstract

The aim of this systematic review was to examine the roles of body image perception and mental health in female athletes participating in aesthetic sports (e.g., dance, gymnastics, cheer). The parameters used to find the existing literature needed included studies that were: published in the year 2020 or after, contained female participants 12 years and older, focused on aesthetic sports, and were written in English. Thirteen articles were ultimately used in this systematic review, of which 62% conveyed that negative body image perception was common across a variety of aesthetic sports and the athletes’ negative body image perception had a significant negative impact on mental health. Eating disorders were a common result of negative body image perception, as shown in 69% of the articles. Common themes of mental health and risks of eating disorders were identified including a hyperfocus on a thin physique, an association with anxiety or depression, and receiving critiques on their body from coaches, peers, family, and social media. Participants in aesthetic sports should be made aware of the association between body image and mental health. Coaches and athletes should collectively aim to emphasize the importance of training and performance rather than physique to help create a healthy environment for participants of aesthetic sports.

Keywords

gymnastics, dance, cheer, body satisfaction, eating behaviors

Introduction

Highly aesthetic sports such as dance, gymnastics, and cheerleading emphasize the figure of the athlete, especially for females (Crissey & Honea, 2006; Kantanista et al., 2018; Siegel, 2007). To achieve competitive success, athletes may be required to maintain a slender figure with very little body fat, placing female athletes under immense pressure to maintain a certain appearance. Evidence suggests that this pressure impacts how female athletes perceive their bodies. Studies have found that the pressure to maintain an ideal appearance for a particular sport negatively impacts a female athlete’s perception of her own body’s appearance (Aleksić Veljković et al., 2020). For example, to maintain a slim figure with low body fat, female athletes will take extreme dieting measures, often leading to an eating disorder (Budzisz & Sas-Nowosielski, 2021; de Oliveira et al., 2021; Jankauskiene et al., 2020). In these cases, the negative body perception has such a large mental impact on athletes that they take extreme and unhealthy measures to achieve the “perfect” body for their sport. In short, athletes’ mental health is affected so much that they disregard their physical health.

Perfectionism and competitiveness are common elements in all sports (Budzisz & Sas-Nowosielski, 2021; Leonkiewicz & Wawrzyniak, 2022; Monteiro et al., 2014), but they manifest themselves in unique ways in sports that focus heavily on body image (Leonkiewicz & Wawrzyniak, 2022). Female ballerinas and artistic gymnasts have been shown to overestimate their body size and see themselves as overweight, creating a false sense of reality (Leonkiewicz & Wawrzyniak, 2022). Athletes’ efforts to maintain a perfect body image for their sport can become quite competitive in nature, as athletes often hold the mindset that “thin is going to win” (Monteiro et al., 2014). The drive to maintain a “perfect” body appearance, fueled by the inherent competitiveness of sports, creates an overwhelming intrinsic pressure on athletes who want to perform exceptionally well in their respective sports. The stress and anxiety created by the pressure appear to have a powerful negative effect on how female athletes view their bodies.

Extrinsic factors, such as social media (Ausmus et al., 2021), physiological discrimination (Crissey & Honea, 2006), and the influence of coaches(Aleksić Veljković et al., 2020) and parents (Kantanista et al., 2018) can provide additional pressure to female athletes around bodily appearance. Social media pressures them to fulfill societal beauty standards, often driving athletes to become their harshest critics as they try to meet multiple demands regarding their appearance. Additionally, in the world of sports, female athletes often face discrimination because of their physiological differences from males, often being viewed as inferior to males in sports performance (Crissey & Honea, 2006). The influence of coaches and family members puts immense pressure on female athletes, to the point that some studies have suggested that such persons avoid talking about the athlete’s body to help prevent the athlete’s development of an eating disorder (Aleksić Veljković et al., 2020; Smith et al., 2022).

For the purpose of the present study, “aesthetic sports” refers to dance, gymnastics, swimming, cheerleading, and ice skating (e.g., competitions with judges). While many participants in non-aesthetic sports may experience both internal and external pressure to perform, there is more of an impact on female athletes in aesthetic sports (Aleksić Veljković et al., 2020; Parlov et al., 2020). Not only do the internal and external pressures on these female athletes have an impact on their body image perception, but the pressure of maintaining thinness among female athletes increases their risk of developing eating disorders (Athanasaki et al., 2023; Bjornsen & O’Connor, 2023; Bruin et al., 2007; Crissey & Honea, 2006; de Oliveira et al., 2021; Mathisen & Sundgot-Borgen, 2019; Smith et al., 2022; Toselli et al., 2022). Eating disorders paired with excessive exercise can lead to consequences such as the reduction of their rate in energy (Athanasaki et al., 2023).

Collectively, there are many factors that contribute to how a female athlete views herself, including coaches’ perceptions and performance. Previous reviews in female aesthetic sport athletes have focused on the relationship between eating disorders (Arcelus et al., 2014; Greenleaf et al., 2009), body dissatisfaction (Arcelus et al., 2014; Wasserfurth et al., 2020), and potential influences as they relate to social media, coaches, and other cultural and external pressures (Blanchard et al., 2023; Holland & Tiggemann, 2016; Wasserfurth et al., 2020). However, there is no summative literature that assesses how an athletes’ body image couples with their mental health among different competitive sports. It is likely that there are similarities in athletes’ experiences among different sports that require aesthetic components. The purpose of this systematic review was to examine the role of body image perception and mental health among female athletes who participate in aesthetic sports.

Methods

Search Process

The literature search used EBSCOhost and SPORTDiscus. Search terms included “body image and mental health in female athletes”, “body image in female gymnasts”, “body image in female swimmers”, “body image in cheer/dance”, “aesthetic sports and body image”, “body satisfaction in female athletes”, and “mental health in female athletes” AND “body image.”

Eligibility Criteria and Selection Process

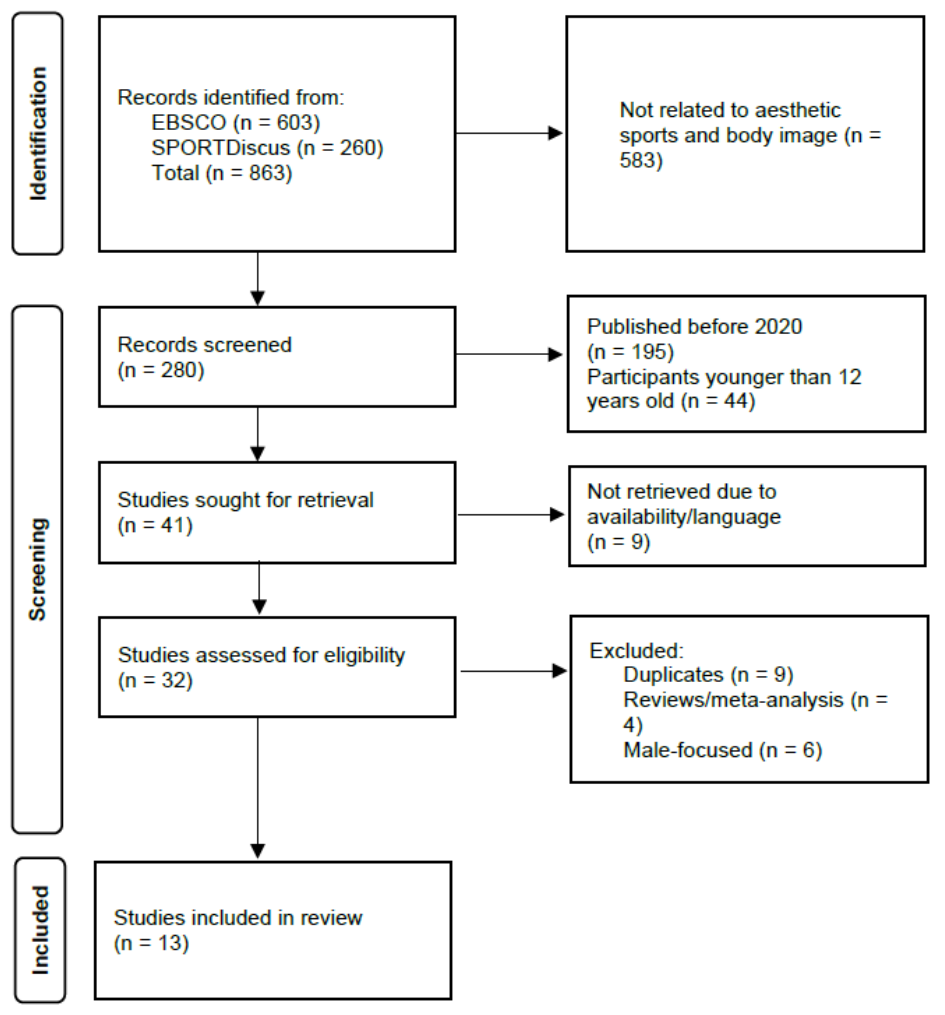

Studies were included if they discussed the concept of an athlete’s body perception in relation to any aspect of their mental health, included female athletes who were 12 years old or older, were published in 2020 or after, were available in English, and available for full text access. Exclusionary criteria were studies that focused solely on males, involved children under the age of 12, included athletes who were not primarily in aesthetic sports as defined by (Kantanista et al. 2018), or were systematic reviews, meta-analyses, or opinions. The researchers screened titles and abstracts of all the relevant articles with the criteria listed above. Figure fig. 1 portrays the system of elimination used for this systematic review. Our initial search produced 863 articles, with EBSCOhost and SPORTDiscus yielding 603 and 260 articles, respectively. Our process of elimination resulted in thirteen articles that were included in this study. These studies consisted of a variety of methods that generated both quantitative and qualitative data, primarily through questionnaires and in-person interviews with participants.

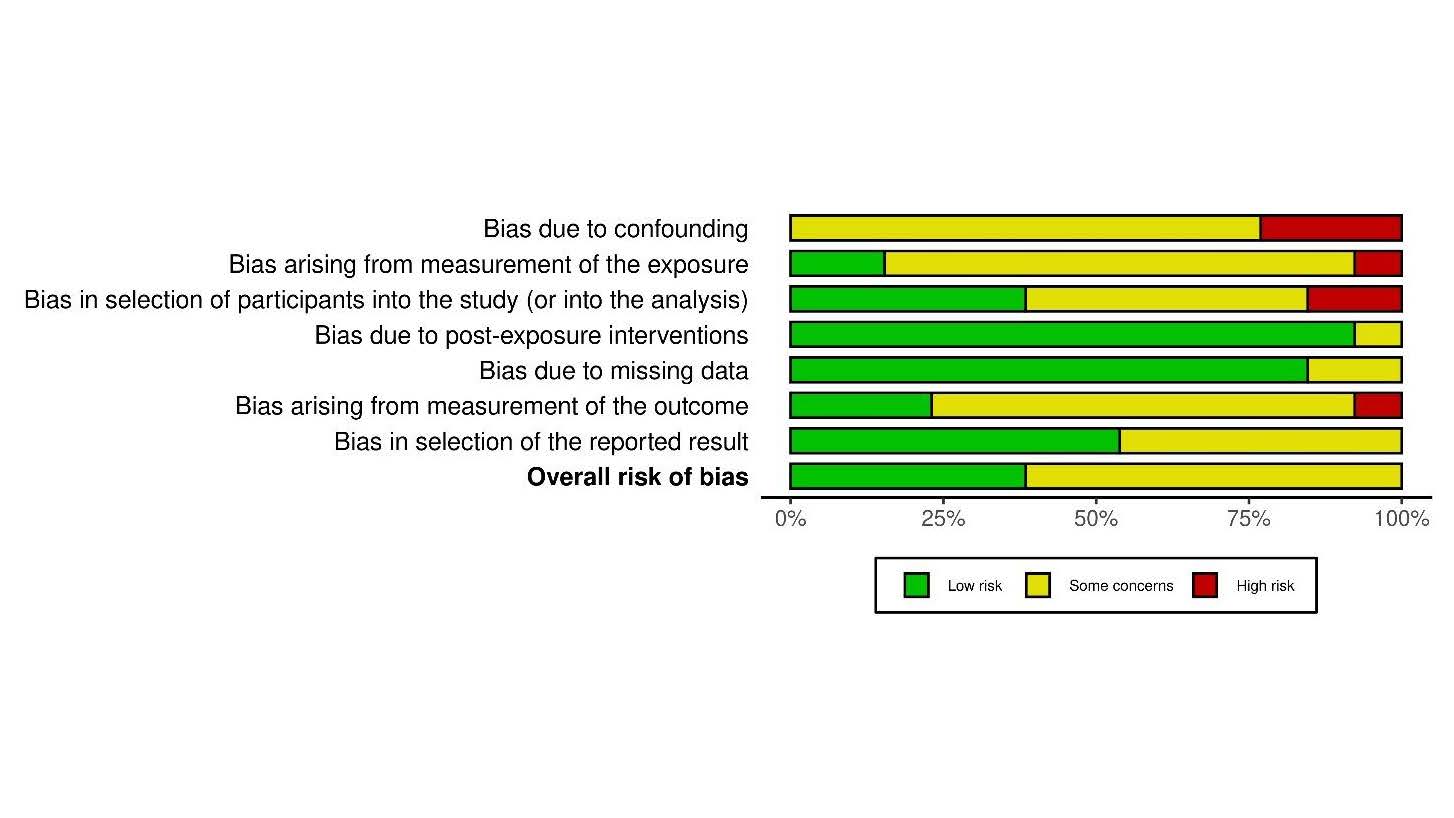

The articles included were qualitatively evaluated using the STROBE checklist for observational and cross-sectional studies, and data was summarized into objectives determined by the authors. Any disparities of opinion on the quality of the studies between two authors were settled by a third. The risk of bias in non-randomized studies – of exposure (ROBINS-E) tool was used to evaluate each study for biases (Higgins et al., 2024). Results of this assessments were plotted using the robvis tool (McGuinness & Higgins, 2021).

Studies were coded based upon 1) if male and female athletes were compared, 2) if aesthetic and non-aesthetic sports were compared, 3) assessments or explorations of disordered eating, eating disorders, or extreme dieting, 4) assessments or explorations of mental health as it related to depression, anxiety, stress, or other concerns, 5) assessments of team influences from the coach or teammates, 6) assessments of other influences such as social media, costumes/uniforms, and use of mirrors in training. Two authors coded each study and discrepancies were settled by a third author. From this coding, several major themes emerged as we reviewed these articles: The prevalence of negative body image perception in female athletes, eating disorders as a result of negative body image perception, other significant mental health impacts of negative body image perception, and external factors influencing body image perception and mental health.

Results

Brief descriptions of each study can be found in Table tbl. 1. Across the thirteen studies included, there were a total of 1,035 female athletes who participated in aesthetic sports. The average age of participants was 18.2 years. The aesthetic sports that female subjects participated in were artistic swimming, synchronized swimming, dance, ballroom dance, modern dance, ballet, gymnastics, artistic gymnastics, rhythmic gymnastics, cheerleading, and figure skating. The experience of the subjects included recreational, club, collegiate, amateur, professional, elite, national, and international.

Study Summary | Age of Participants | Sport | Level of Play | Total Number of Participants | Results |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

18 - 25 | Gymnastics | Club or Collegiate | 72 | Body image dissatisfaction: 23.6% | |

12 - 30 | Artistic Swimming, Gymnastics, Dance | National and international | 241 | Adolescent Athlete Eating Disorder Risk: 14.9% Adult athletes Eating Disorder Risk: 6.9% | |

> 18 | Ballroom Dance | Professional | Male: 187 Female: 133 | Body dissatisfaction for women: 65.4% Eating Attitudes Tests (11.18.18 ± 9.31 out of 78 points) Bulimic Inventory Test Edinburgh (7.01 ± 4.82 out of 30 points) | |

13 - 16 | Gymnastics | National | 28 | Some gymnasts reported that they were satisfied with their body, while others showed dissatisfaction. They mentioned an increase in body weight and physical characteristics that displeased them. | |

14 - 18 | Dance | Competitive | 12 | All participants experienced negative physical and emotional repercussions throughout dance. Dancers' environment, parents, coaches, and peers had a large effect on the dancers’ relationship with body image. | |

12 - 19 | Rhythmic Gymnastics | National | 18 | EAT - 26: 44.4% Body image distortion: Not present: 38.9% Mild distortion: 33.3% Moderate distortion:27.8% | |

Mean Age: 12.76 ± .93 years | Rhythmic Gymnastics | National | 40 | Correlation between the BSQ and EAT26 test is positive (.511) as well as Dieting (.932) | |

College-age | Dance | Collegiate | Female: 184 Male: 14 | Anxiety and Depression: 37.9% Eating Disorder History: 9.1% | |

Mean Age: 19.39 years | Modern Dance and Ballet | Not specified (most classes were just for fun for participants) | Modern Dance: 31 Ballet: 36 | Decreased body image satisfaction Pretest mean: 3.57 Post-test mean 3.45 Decreased mid-torso satisfaction in ballet: Pre-test 3.24 Post-test: 2.8 | |

13 - 16 | Artistic Swimming, Water Polo | Competitive | Artistic Swimming: 36 Water Polo: 34 | Artistic swimmers EAT- 26 score: (C = 11) Waterpolo EAT-26 score: (C = 8) | |

12 - 18 | Gymnastics, Skating, Dancing | Not specified | 142 | Body image-related perfectionistic self-presentation mediated an association between body image-related cognitive fusion and disordered eating. | |

16 - 23 | Aesthetic: Artistic and Rhythmic Gymnastics, Dance, and Synchronized Swimming Non-Aesthetic: Volleyball, Soccer, Basketball, Track and Field | Club | Aesthetic: 54 Non-Aesthetic: 66 | Aesthetic BMI: 20.54 EAT- 26 Score: 10.52 Non-aesthetic BMI: 21.84 EAT- 26: 8.23 | |

24 - 29 | Artistic Gymnastics, Rhythmic Gymnastics, Artistic Swimming | National | 8 | Qualitative study The athletes shared their negative experiences with critiques about their body |

Out of the thirteen articles, one (7.7%) found that female athletes are more susceptible to having a negative body image perception than males in aesthetic sports (Cardoso et al., 2021); two (15.4%) found that athletes in aesthetic sports are more susceptible to having a negative body image perception than athletes in non-aesthetic sports (Aleksić Veljković et al., 2020; Parlov et al., 2020); nine (69.2%) found correlations between participation in aesthetic sports and negative body image perception that led to eating disorders (Aleksić Veljković et al., 2020; Borowiec et al., 2023; Cardoso et al., 2021; Jardim et al., 2022; Markovic et al., 2023; Michaels et al., 2023; Paixão et al., 2021); eight (61.5%) found correlations between negative body image perception in aesthetic sports and poor mental health (conditions other than eating disorders) (de Oliveira et al., 2021; Doria & Numer, 2022; Jardim et al., 2022; Markovic et al., 2023; Michaels et al., 2023; Paixão et al., 2021; Radell et al., 2020; Willson & Kerr, 2022) and five (38.5%) found that negative body image perception in aesthetic sports often stemmed from outside influences such as coaches, judges, and social media comments (Ausmus et al., 2021; de Oliveira et al., 2021; Doria & Numer, 2022; Michaels et al., 2023; Radell et al., 2020; Willson & Kerr, 2022).

The results of the risk of biases assessment are shown in Figure fig. 2. Most of the studies were low risk or had some concerns of biases. The areas of greatest biases were related to self-report of variables through surveys and cross-sectional studies, allowing for biases of confounding variables and researchers not exploring the volume and intensity of exposures to cultures of aesthetic sports, social media, and other potential negative influences. Some studies reported limitations in study sample size and participant selection across different sports. This component of biases may have been limited by the number of qualitative studies included in the systematic review.

Discussion

This systematic review examined the roles of body image perception and mental health in female athletes participating in aesthetic sports. Thirteen studies reviewed included artistic swimming, synchronized swimming, dance, ballroom dance, modern dance, ballet, gymnastics, artistic gymnastics, rhythmic gymnastics, cheerleading, and figure skating. Common themes related to negative body image, disordered eating, and external perceptions were seen across several studies. Each of these concepts are detailed below.

Prevalence of Negative Body Image Perception in Female Athletes

Only one article included in this study offered a direct comparison between male and female athletes in aesthetic sports (Cardoso et al., 2021). This was a cross-sectional study examining body image dissatisfaction and eating disorders in male and female ballroom dancers. Data included an assessment of body image satisfaction, the Eating Attitudes Test (EAT-26), and the Bulimic Inventory Test Edinburgh (BITE). Female participants were generally more dissatisfied with being overweight than male participants, and women were found to have a 96% less chance of being dissatisfied due to being underweight than men, indicating that female athletes are more tolerant of being underweight than males. The study also found that participants who scored higher on the BITE assessment had a 28% greater chance of having high body dissatisfaction, although it should be noted that the study did not specify that this was solely a female participant characteristic.

Three articles examined the impact of body image perception on athletes participating in aesthetic sports versus athletes participating in non-aesthetic sports. A comparison of female athletes from aesthetic sports (synchronized swimming, artistic and rhythmic gymnastics, and dance) to female athletes from non-aesthetic sports (volleyball, track and field, and soccer) found that aesthetic athletes scored significantly higher on a body image dissatisfaction questionnaire than non-aesthetic sport athletes (Aleksić Veljković et al., 2020). Additionally, 35% of the aesthetic sport participants showed signs of an eating disorder, compared to none in the non-aesthetic group (Aleksić Veljković et al., 2020). This finding was echoed by a second study that revealed higher eating disorder risk in female artistic swimmers compared to female water polo players (Parlov et al., 2020). The third study’s findings contradicted the aforementioned studies, finding that non-aesthetic sports such as karate and taekwondo requiring a lean body showed higher risk for eating disorders than aesthetic sports (Borowiec et al., 2023). Interestingly, two forms of swimming were included into both the aesthetic and non-aesthetic category in this study. The authors speculated that the higher risk for eating disorders in this case was due to weight-cutting measures employed in lean non-aesthetic sports that were not the result of body image dissatisfaction. These results suggest that athletes from both aesthetic sports and from sports requiring weigh-ins or a lean body type have a higher prevalence of negative body image perception compared to athletes from non-aesthetic sports. This pursuit of a certain body image often results in low energy availability, which may then slip into disordered eating (Wasserfurth et al., 2020). Future studies should consider if treatment options for negative body image are similar between aesthetic sports and lean body type sports requiring weigh-ins.

Eating Disorders as a Result of Negative Body Image Perception

It became clear during the article search that eating disorders were the most studied mental health outcome of negative body image perception in aesthetic sports, aligning with previous literature reviews (Holland & Tiggemann, 2016; Wasserfurth et al., 2020). Nine studies (69%) included in this review either mentioned or examined eating disorders in aesthetic sport populations. Of those that examined eating disorders, four studies found correlations between negative body image perception/body image distortion and risk for eating disorder (Aleksić Veljković et al., 2020; Borowiec et al., 2023; Markovic et al., 2023; Paixão et al., 2021). Three studies showed that aesthetic sports participants were at risk for or displayed signs of an eating disorder when questioned in an interview or given a standardized eating behavior questionnaire (Aleksić Veljković et al., 2020; Jardim et al., 2022; Willson & Kerr, 2022). Other findings included aesthetic sport athletes using extreme dieting as a way to meet body shape expectations within their sport (Willson & Kerr, 2022), correlations with perfectionistic attitudes regarding body shape and disordered eating (Paixão et al., 2021), high readiness to use extreme dieting measures in aesthetic sport participants (Aleksić Veljković et al., 2020), and correlations between participation in an aesthetic sport and eating disorder risk (Parlov et al., 2020). The idea of “thin to win” resonates from previous literature suggesting that body dissatisfaction often manifests into disordered eating (Wasserfurth et al., 2020). Suggestions in helping athletes at a greater risk for these disorders, regardless of sex, include teaching flexible eating behaviors that focus on nutrients and an evaluation of their social environment (Wasserfurth et al., 2020).

Other Mental Health Impacts of Negative Body Image Perception

Eight of the thirteen articles (62%) discussed a variety of other mental health impacts that negative body image perception can have on athletes. Anxiety and depression were common among aesthetic athletes (Michaels et al., 2023) and often accompanied eating disorders. Several studies revealed that stress was a major factor when athletes were unsatisfied with their bodily appearance, whether it resulted from the athlete’s own perception of their bodies or pressure placed on them by coaches, peers, and judges (Doria & Numer, 2022; Willson & Kerr, 2022). Female dancers claimed that stress and pressure regarding their bodies were the source of their negative body image perception (Doria & Numer, 2022), and rhythmic gymnasts claimed that they had difficulty reconciling the body image imposed upon them by their sport with the body image found attractive by society since these two images were often quite different (de Oliveira et al., 2021). Chronic stress exposure and elevated cortisol levels are linked with increased incidences of anxiety, depression, low energy availability, and risk factors of the female athlete triad (Wasserfurth et al., 2020).

Body image distortion or seeing one’s body negatively, irrespective of how one’s body actually looks, was mentioned or examined in several studies. Body image distortion correlated with poor body esteem (Jardim et al., 2022), body image-related perfectionism and eating disorders (Paixão et al., 2021). These results align with previous findings in dancers, suggesting that high self-standards, low self-esteem, and perfectionism all had links with disordered eating behaviors (Arcelus et al., 2014). One study found that 61.1% of rhythmic gymnasts displayed some degree of body image distortion (Jardim et al., 2022). Athletes who struggled with negative body images often showed signs of harmful perfectionistic attitudes regarding their bodies (Markovic et al., 2023; Paixão et al., 2021). De Oliveira et al. (2021) found that this perfectionistic attitude often led to athletes comparing themselves to other more successful athletes with an “ideal” body shape. Perfectionism was shown to be associated with body image distortion, eating disorders (Paixão et al., 2021), and negative body image perception (Markovic et al., 2023). Athletes reported that a negative body image perception, often caused by pressure from coaches and peers, led to decreased enjoyment of their sport (Willson & Kerr, 2022).

Negative Body Image Perception and Outside Influences

Several external factors were found to influence or bring about a negative body image perception in female aesthetic athletes. Five articles (38%) discussed outside influences on body image that had a negative impact on athletes’ mental health. Pressure from coaches appeared to be the predominant external cause of negative body image. One interview-based study found that the participants, all aesthetic athletes, including several Olympians, were frequently body-shamed by their coaches. This shaming played a large role in their issues with negative body image perception (Willson & Kerr, 2022). Two additional studies’ participants mentioned the pressure put on them by coaches to maintain a certain body shape as being a major cause of negative body image perception (de Oliveira et al., 2021; Doria & Numer, 2022). Wasserfurth et al. (2020) has previously shown that coaches should refrain from negative comments and aim to maintain a healthy coach-athlete relationship that includes appropriate nutritional strategies that lead to optimal performance. Since most aesthetic sports are judge-based, the way a judge evaluates an aesthetic athlete’s body can directly affect their performance in competition. Judge’s opinions were found to be another influence on negative body image perception, as it was directly tied to the athlete’s success in their sport (de Oliveira et al., 2021). Pressure from coaches and judges placed athletes under added pressure to maintain a certain body shape, making them more prone to extreme dieting measures and at risk for eating disorders (Willson & Kerr, 2022).

Interestingly, two studies explored the effect of mirrors on body image perception. The use of mirrors in dance studios was found to cause a hypercritical attitude in many study participants regarding their bodies, as they were constantly viewing them from many different angles, leading to negative body thoughts and even hatred of their bodies (Doria & Numer, 2022; Radell et al., 2020). Costumes were also mentioned by some participants as a source of negative body thoughts, as they often had to conform not only to the body shape standards of their sport but fit well into the costume required by their performance (Doria & Numer, 2022). Further research in this area is needed to corroborate these findings.

One study examined the effect of injury on body image in collegiate dancers. The survey results revealed that dancers with an active injury were at higher risk of developing an eating disorder, likely because they were not actively maintaining their required body shape through training during their injury period. The results of this study included a correlation between eating disorder history and active injury status in the dancers (Michaels et al., 2023). Outside of injury, athletes reported that they resorted to extreme weight control methods via dieting because that was under their control, unlike many other factors that affected their body shape (Willson & Kerr, 2022).

Social media proved to be a harmful influence on body image perception in aesthetic athletes (Ausmus et al., 2021). Collegiate gymnasts showed a strong correlation between the amount of negative social media comments received about their bodies and eating disorders, with 23.6% of the participants in the study scoring high on a body image dissatisfaction questionnaire. Additionally, a correlation was found between disordered eating and the severity of the athletes’ emotional reaction to said comments. These results align with literature in adolescents and non-athletes, indicating the negative effects of social media use on disordered eating symptoms, mental health, and body dissatisfaction (Blanchard et al., 2023; Holland & Tiggemann, 2016). The combination of social media use with adolescents competing in aesthetic sports, places an even greater risk for body dissatisfaction and other negative outcomes. More research needs done in this specific area to assess the scale of these effects and if policy interventions for adolescents should be considered.

Limitations

Limitations for this systematic review include low overall n-size, biases of self-reported data, using only studies published in English and after 2020, and methodology differences across the studies. Collective sample size of the studies was only 1,035 female athletes participating in aesthetic sports, which may limit the external validity of the findings. Reliance on self-reported data through questionnaires and interviews introduces potential for recall and social desirability biases. Due to the cross-sectional design of many studies, conclusive causal relationships between body image and mental health outcomes cannot be made. Choosing only literature in English and published after 2020 may have excluded relevant research published in other languages or earlier. Lastly, the different versions of the EAT survey used across studies also pose challenges in synthesizing the results.

Conclusion

Due to aesthetic sports heavily favoring aspects of beauty and thinner physiques, female athletes tended to hyperfocus on their body image to succeed in competition. Negative body image perception often led to an increased risk of developing eating disorders, which were often the result of or accompanied by anxiety and depression. Critiques regarding the athlete’s body from certain social media, their peers, family, and coaches also reinforced these notions that cause athletes to develop an eating disorder. Preventative measures should be taken so the athlete can participate in sports without harming their mental or physical health. These measures include creating a positive environment centered on performance outcomes, de-emphasizing how the athlete looks, reducing the use of mirrors in practice, and ensuring the athletes have access to mental healthcare professionals and dietitians.

Future studies should aim to find and cohesively generate quantifiable data regarding exactly how many female athletes’ mental health is negatively affected while they are participating in aesthetic sports. While this study included articles from all over the world, only thirteen were eligible. Of those thirteen articles, five used a form of the Eating Attitudes Test (EAT) as part of their results (Aleksić Veljković et al., 2020; Cardoso et al., 2021; Jardim et al., 2022; Markovic et al., 2023; Parlov et al., 2020) while the rest had different ways of interpreting their data. Solutions to reducing the correlation between negative self-perception, poor mental health, and eating disorders rely on knowing how many athletes are truly affected. Additionally, many studies focus on eating disorders without taking into account other mental health issues that may be the result of a negative body image perception. While eating disorders are one of the most severe outcomes of a negative body image perception, they are not the only outcomes, as was displayed in several of the studies featured in this review. Anxiety, depression, stress, body image distortion, and pressure from many sources were discussed in this review. Future studies should look beyond eating disorders and examine some of these other issues revolving around body image. Furthermore, while problems such as pressure from coaches and eating disorders have been identified, more research is needed as to how these issues affect athletes’ performance and how we can reduce or eliminate these issues that plague athletes participating in aesthetic sports.